Cold

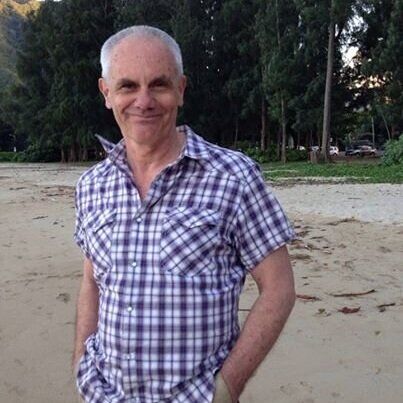

Don Stoll

Richard had become a father four times when he was in his twenties and thirties. By the time he was sixty, he thought he had finished with all of that. Therefore, by the time he was sixty, having become the father of an entire African village seemed strange to him.

The fact that the villagers called him “Father”—Baba, because even the handful who spoke English preferred Swahili—pleased and embarrassed him. But above all it astonished him. His wife, though similarly astonished and embarrassed by having become “Mother”—Mama—was far beyond pleased.

Peggy had dreamt of visiting Africa since her childhood. She was eight years old when she saw a movie about a man and a woman, not from Africa, who rescued orphaned lion cubs. She dreamt that one day she would do the same. But as she grew older, she realized that this land of incomparable beauty was also inhabited by human beings. She dreamt of meeting them.

Then, Peggy met Richard. She fell in love with him and married him. Together, they had four children. Their needs came before everything else. Peggy was more than fifty years old before she realized her dream of Africa. When she did, she struggled to make sense of a place whose reality surpassed her dreams.

The lions and elephants and giraffes possessed the elemental beauty she had expected. She had not expected the human beings to possess an elemental beauty of their own.

In a village an hour or two off of the safari circuit, she and Richard had met the people. They had nothing but gave everything. They drank milky tea and ate maize and beans and tasteless bananas three times a day. Sometimes they ate eggs. Yet for Peggy and Richard they bought cases of Fanta and Coca-Cola, and they sacrificed chickens for their meat. They labored constantly to survive and often walked laden with firewood collected from the forest or with buckets of drinking water scooped out of streams soiled by oxen and milk-goats, but they never admitted to exhaustion. Their days were marked by routine and repetition but they never admitted to boredom.

Even their celebrations were marked by the tireless repetition of movement and music: of dancing that meant only jumping up and down, and of the same songs over and over again. A thousand times, Peggy and Richard would hear “We are celebrating Peggy, we are celebrating Peggy,” and “We are celebrating Richard, we are celebrating Richard.” Dozens of times, they would be draped in woolen robes as the people sang that a gift is a gift, no matter how small. Peggy and Richard did not think of the woolen robes as small gifts because they were given by people who had nothing. They marveled at the generosity and they marveled at the tolerance of routine and repetition. Peggy suggested that they experienced it not as boredom, but as affirmation.

She regarded this as speculation rather than understanding, however, because she had come from such a very different place. She had come from a land of plenty that advertised itself as replete with both the desire and the capacity to escape exhaustion and boredom. The villagers were unlike any people she’d ever known. There were aspects of her life that they might never understand.

Yet they understood one crucial thing about her. The needs of her four children, now adults, had not used up her generosity because her generosity was inexhaustible. The need to take time for herself, urged upon the residents of the land of plenty by their most trusted counsellors, was something Peggy could not find in herself.

She would be unable to remember if she had already announced to herself that she felt at home in Africa when the villagers assured her that she had come home and that her return to the land of plenty must therefore be temporary.

She must come back to the village, its people told her, because they needed new schools, a medical clinic, clean water, and much more. They could see that she wished to bring these things.

Many years after that first visit, Richard would still wonder what wishes the villagers had thought they saw in him. He would wonder about this because he did not know himself what wishes he’d harbored, except for the wish to make Peggy happy.

During their first few years of raising money for new schools and a medical clinic and clean water, Richard struggled as his wife did to make sense of the elemental beauty of the villagers. Both Richard and Peggy could see that the beauty was tied to an elemental faith in God that gave assurance of riches where only poverty was visible, of strength when the last drop of strength ought to have been consumed, of joy where the prevailing wisdom of the land of plenty would have discerned only drudgery.

But Richard believed there was no God. He thought that no God worthy of the name would have tolerated the coexistence of a land of plenty with a people who had nothing. The villagers’ faith in God gave him trouble.

He reconciled himself to their faith by lagging far behind his wife in the acquisition of Swahili, so that their speech about God was muffled for him. One year, when Peggy couldn’t get away from work, Richard traveled to Africa alone. The village leaders sent a man named Samuel to collect him from the airport. Throughout the drive of four hours, Samuel played music: the same song, in a popular African style that Richard couldn’t put a name to, repeated fifty or a hundred times. Richard understood only the refrain: Mungu yuko hapa, “God is here.” It was a Christian song. He knew he would have hated it if the words had been in English. Yet, long before the end of the drive, he had decided that he loved the song.

Richard wondered if the moral beauty of the people would have been able to coexist with the absence of faith. He couldn’t decide on an answer. But he feared that he might not like the answer because he valued truth as much as he valued beauty.

This fear was far from his mind one luminous morning some five years after the realization of Peggy’s childhood dream of Africa. As the villagers prepared to say farewell till next year to her and Richard, he felt especially well disposed toward them.

Overnight, torrential rains had transformed the village’s dirt roads into nearly impassable rivers of mud. Yet the rainfall had not dampened the beauty of the people, who had turned out en masse to see off their father and mother. Beneath a brilliant sky and a baking sun, they stood in the reeking mud or sat on the wet grass while one church choir after another performed and while one speaker after another upped the ante of praise for the village’s father and mother.

Richard asked Peggy if he could give his own speech before hers so that he wouldn’t have to follow her wealth of Swahili with his single phrase. He would start with his Swahili phrase. That way, he could dwell upon the safe ground of English for the balance of his speech. In English, he would celebrate completion of the latest project for which he and Peggy had raised money: a new bridge over the river flowing through the village. Every rainy season, when the river rose, it had submerged the old bridge and sliced the village in two.

“God bless you,” Richard would begin. He knew the Swahili: Mungu awa bariki. What harm could it do to ask for the blessing of a nonexistent God upon people who had so little?

But when he spoke the words, the people laughed.

He was standing next to Peggy, who was seated. She whispered to him.

“You said Mungu awa baridi. That means ‘God be cold.’”

Richard felt exposed.

But only for an instant. The people had not interpreted his mistake as an attempt to smuggle Nietzsche into the village. The pronouncement of the death of God would have been literally unintelligible to them; it would not have registered. The people were laughing not in mockery of his atheism, but in appreciation of his attempt at Swahili.

He joined in their laughter before continuing his speech in English.

© 2020 Don Stoll

About the Author

In 2008, Don Stoll and his wife founded their nonprofit (karimufoundation.org) to bring new schools, clean water, and clinics emphasizing women's and children's health to three contiguous Tanzanian villages. Don is a Pushcart-nominated writer whose fiction is forthcoming in THE BROADKILL REVIEW, WILD VIOLET, NORTHWEST INDIANA LITERARY JOURNAL, SARASVATI, DOWN AND OUT, HOOSIER NOIR (twice), BRISTOL NOIR, COFFIN BELL, YELLOW MAMA, and FRONTIER TALES, and has recently appeared in XAVIER REVIEW, THE MAIN STREET RAG, THE GALWAY REVIEW (tinyurl.com/y6nxt9nv, tinyurl.com/y4vdsqhe), GREEN HILLS LITERARY LANTERN (tinyurl.com/y2lfxysm), MINUTE MAGAZINE (tinyurl.com/uhwu28n), BETWEEN THESE SHORES, HEART OF FLESH (tinyurl.com/th44enr), THE AIRGONAUT (tinyurl.com/y67mzfmv), A NEW ULSTER, PUNK NOIR (tinyurl.com/y5o2x5fz, tinyurl.com/uwyz7jb), BRISTOL NOIR (tinyurl.com/uzuzo6o), HOOSIER NOIR, CLOSE TO THE BONE (tinyurl.com/y38ac6jv, tinyurl.com/sc9btxl), HORLA (tinyurl.com/y3k6eewx), YELLOW MAMA (tinyurl.com/sqyt5qr and two stories at tinyurl.com/y5yzozel), FLASH FICTION MAGAZINE (tinyurl.com/vcmpa3f), PULP MODERN, DARK DOSSIER (four times), THE HELIX, SARASVATI, SAGE CIGARETTES (tinyurl.com/yyotrtsb), ECLECTICA (tinyurl.com/y73wnmgq), EROTIC REVIEW (tinyurl.com/y8nkc73z, tinyurl.com/y36zcvut), CLITERATURE (tinyurl.com/y5m8arzn), HORROR SLEAZE TRASH (tinyurl.com/qno5ucu), DOWN IN THE DIRT, and CHILDREN, CHURCHES AND DADDIES.